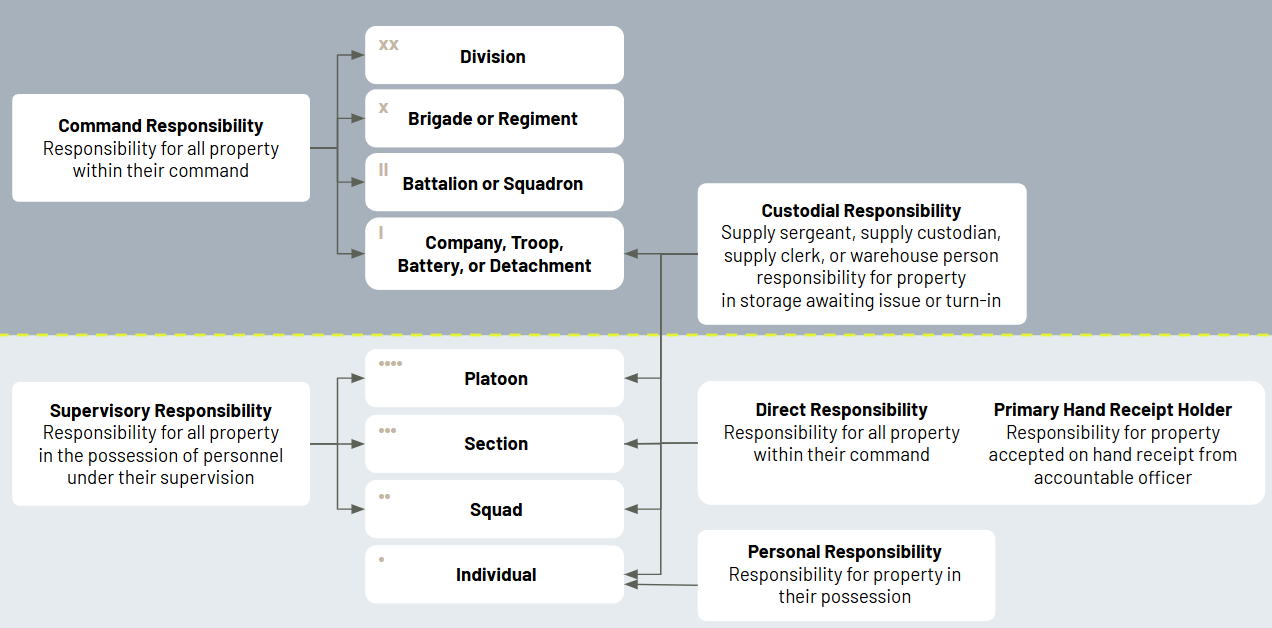

The Adyton Operations Kit (AOK) is a suite of mobile defense products built for the warfighter that digitizes and automates operational processes, generating new, real-time data about personnel, equipment, and munitions and increasing readiness, operational agility, and lethality of America’s forces — while saving taxpayer dollars.

AOK is built to support the most highly sensitive information, including classified data up to the Secret level. AOK has also been tested and cleared to handle the most sensitive unclassified data, like mission-critical information or sensitive defense systems, able to securely operate on both personal and government-furnished devices. It is imperative the Pentagon enables soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and guardians to digitally manage personnel, equipment, and munitions rather than doing it on pen and paper — in other words, extending our military’s information systems to extend to the individual, a capability our military currently lacks.

At Adyton, we believe a BYOD, or “bring your own device,” policy — allowing troops to use their own phones — is the most efficient and direct way to 1) drive widespread, natural adoption of process digitization, 2) improve the quality of information leaders use to make decisions and 3) improve the efficacy and quality of life of every single man and woman serving in our military. The only other alternative is spending billions to procure government-issued phones for every service member, to say nothing of the annual recurring costs of phone and data plans, and coach every single user to understand which devices are best for digitizing which processes.

Budgets are shrinking and the Pentagon is emphasizing speed-to-deployment for technology. Buying every servicemember GFEs is frankly a non-starter.

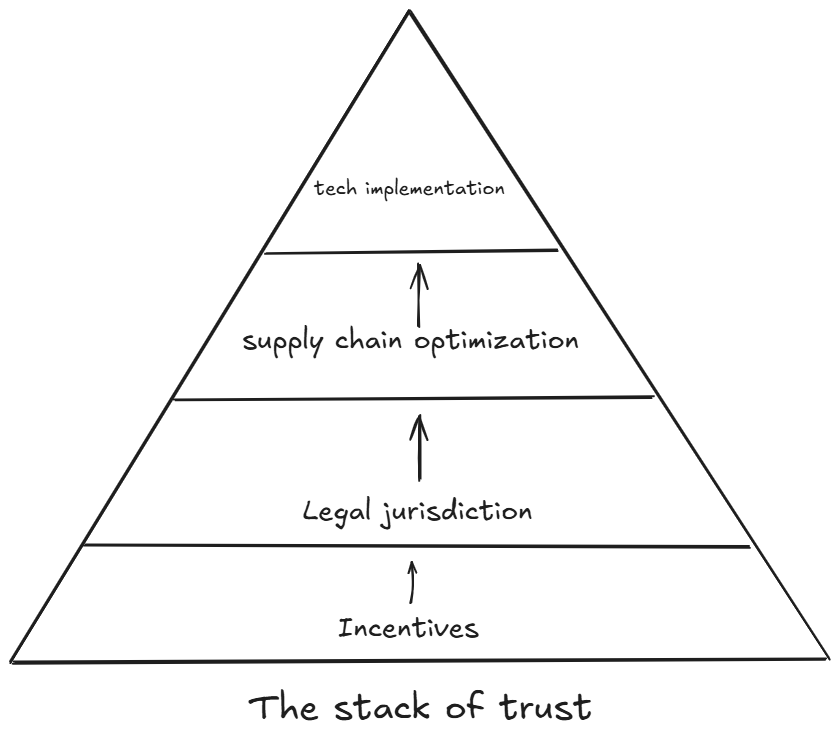

However, we recognize secure military information on a personal device can cause some to balk. When managing sensitive data of any kind, especially for the Department of Defense, trust is paramount. While there are technological components to trust like underlying security protocols and engineering a secure architecture, we take a much broader view, which we call the Stack of Trust (SoT).

At its most basic, the four phases of the Stack of Trust is a model for government agencies, when working with technology providers, to evaluate trust, represented below.

At a slightly more complex conceptual level, the Stack of Trust is meant to show how software providers can implement strong security measures to protect attack surfaces regardless of device. Whether it’s government-furnished Android phone or a personal iPhone, whether it’s a government-issued iMac or a personal PC, areas of risk in software are known and include, but are not limited to: the cloud service in which the application is hosted, the network through which the individual accesses the application, the security of the hardware (i.e., the device), the firmware and operating system on the device, and the actual security of the application.

If a software provider executes the Stack of Trust well, their software will have a robust security posture on any device that meets the requisite standards.

Phase 1: Incentives

At the base of the stack of trust are incentives. As a technology provider for the Pentagon, we have an incentive to build trusted, secure technology. Adyton was founded by veterans, meaning we share a mission intimacy with the military and our nation’s ideals; we have an incentive to build technology for warfighters that works and helps them keep, and our nation as a whole, safe. We also have a financial incentive to take every conceivable step to ensure AOK is safe and secure.

Fundamentally, if a person or organization does not have strong incentives to create trust at the outset, there is no need to assess the underlying technology, because trust cannot be built on misaligned incentives.

Phase 2: Legal jurisdiction

The legality of operations is a mechanism of trust enforcement across two dimensions. The first legal question is, “is this person or entity allowed to do this thing?” In Adyton’s case, it’s pretty simple: We are American citizens at an American company, and therefore can legally build technology deployed with the American military.

The second dimension is legal enforcement: If there is a breach of contract or a person or company otherwise breaks the law — if someone violates trust — they can be sued or barred from doing business with the U.S. government.

The rule of law, and strictures placed on people and organizations working with the Pentagon, then, provide the Pentagon with another layer of trust. Simply put, you can expect most organizations to act within the bounds of the law because they do not want to be punished. However, assuming the existence of laws leads to 100 percent adherence to them is naivety, which is why underlying technological components must also be assessed and validated.

Phase 3: Supply chain optimization

Almost every single business that makes a product takes inputs and components from other producers to assemble the final product. Understanding a given organization’s supply chain security — how safe are the components that go into the product that they themselves do not make or source — is a critical aspect of building trust.

We think about supply chains most often when it comes to the movement of physical goods. If a weapons manufacturer requires a certain kind of steel for howitzer shells, it’s worth asking: Where do they get their steel from? What are the geopolitical and global trade variables that could impact the availability or cost of that steel? Do they have multiple suppliers and supply chain redundancies? We see supply chain risk manifest itself most acutely in very complex systems: for example, Govini reports that “over 40 percent of the semiconductors that sustain DoD weapons systems and associated infrastructure are now sourced from China,” America's number one geopolitical adversary.

But software represents supply chain risks, too. Software developers use coding languages they didn’t develop and deploy software libraries created by third parties, so the software supply chain must be protected.

Phase 4: Implementation and distribution

Phase four includes both implementation and distribution. Think of implementation as the pieces of the supply chain coming together — for physical goods, like a car, that is everything from the onboard computer chips and sensors to transmissions and fuel systems. For software, it is the construction of the underlying architecture and components to build a product.

After a technology provider has assembled its pieces and built a product, it puts that product into the world. For a product like Adyton’s, it’s delivered via the Google Play or Apple App Stores. Some software are cloud-based SaaS platforms; other software runs natively in web browsers. Other software runs on servers and users access the tool through a client. Sometimes IT pushes software to devices, and other organizations use microservices architecture for containerized delivery of software. Regardless of the specific methodology, how a technology is implemented, or delivered, is the final phase in the Stack of Trust.

The Stack of Trust at Adyton

If you'd like detailed literature on Adyton's security posture and protocols, email us from your .mil email: info@adytonpbc.com

.png)